Lizet Dingemans - Artist Spotlight

Tuesday 20 September, 2022

Lizet Dingemans teaches representational art. Yet it’s the ambiguity – the gap between outside reality and the brain’s reconstruction of that reality – that particularly fascinates her.

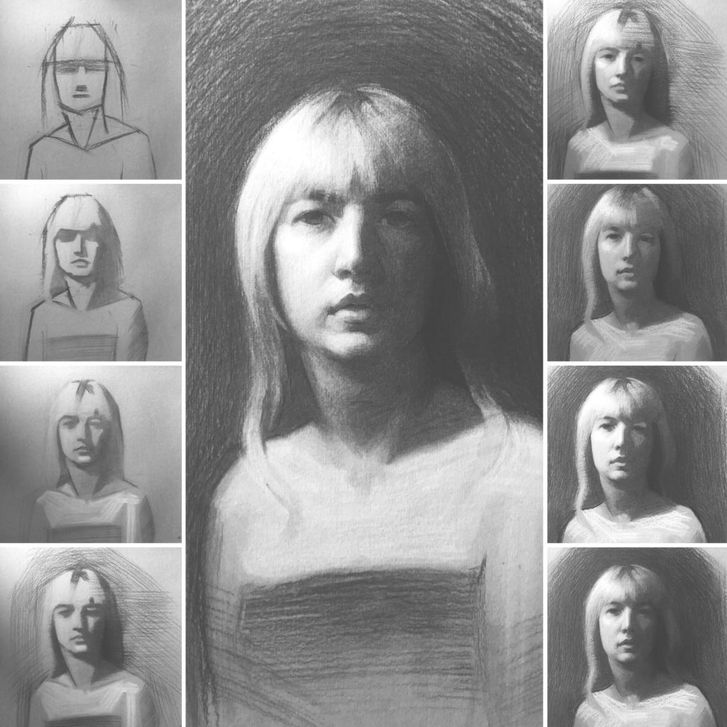

When she speaks with new students, keen to learn traditional skills, she first helps them ‘unlearn’ their ways of seeing the world. ‘When they’re drawing an eye, they’ll draw all the eyelashes,’ she explains. ‘We won’t see every eyelash, but we draw them because we know they’re there. Turning off these ways of interpreting the world is what’s important.’

But Lizet’s ambiguity goes further – into the very concept of beauty. When, as a student herself, she was tasked with producing a still life, she took it as a challenge. This had to be about more than drawing a pot or bowl of fruit. ‘I went to Borough Market in London, where they were selling partridges off the hunt, and I thought: That’s way more interesting’.

One of her first still lifes was a huge dead duck.

She laughs. LARA – the former London Atelier of Representational Art where she was studying – wasn’t impressed. ‘They gave me my own room because the duck was smelling so badly. I painted it for three days, over the weekend… I have to say that after a while you don’t notice the smell!’

Next was an octopus from the fish stall. ‘Absolutely fascinating, and really satisfying to paint, so I got addicted.’

Although she protests – quite rightly considering the breadth of her work – ‘I don’t want to be pigeon-holed as Lizet-Who-Paints-Dead-Animals’ – there is nevertheless something intriguing here.

While she was warned that no one in their right mind would buy a ‘morbid’ picture, Lizet proved tutors wrong. She won an award from the Mall Galleries for her squid and partridge. What’s more, not only did her work sell; and not only did she challenge a ‘pot-and-fruit’ still-life conceit; she also challenged a basic taboo.

‘I love animals – and this is just a practical way to paint them. But it doesn’t mean they’re any less gorgeous in death. And I think that’s another reason why we like these paintings: because we don’t want to talk about death. But death can also be beautiful. I’ve always wanted to go to a mortuary and paint, though I understand that would be difficult to arrange.’

Some 10 years later, Lizet is still being proven right. ‘I’ve recently sold a bee painting. Bees often die at the end of a season, and I think – Are they just going to lie there and rot? I guess it’s another way to go on appreciating them – to give new life to something.’

************

Lizet Dingemans protests. She doesn’t relish talking about herself. ‘Like a lot of artists - that I know at least - we are all kind of introverted.’

It’s genuine modesty, but misplaced. For much of what she says – like her classes - blindsides you with a different way of looking at the world.

She grew up in a small village in the Netherlands, where she’d spend hours watching wildlife. ‘I got obsessed with ants; massively interesting animals. They’re a bit like humans, aren’t they, the way they work; the way they build farms.’

Pets were another passion – though not wholly successfully. ‘We got a male and a female guinea pig, who made four babies… who made four babies the month after! One summer, we let them loose and ended up with this out-of-control herd of guinea pigs roaming the garden.’

She toyed with the idea of studying animal behavioural psychology, but two things stopped her. The first was a personal one: ‘I realised that for people who studied animals [in Holland], it was more commercial; they were less my sort of people. Whereas I always feel at home with people in the art world.’

The second was the Dutch educational system that separated so-called intellect from anything manual. In other words, a system that mitigated – in Lizet’s view - against the very nature of art. ‘In Holland, they make you do an IQ test at 13. As a result, I was put into the highest level. But I’ve never been an academic, so I just didn’t study; it wasn’t my thing. I spent school surviving. As a result, I dropped down the levels, which meant I couldn’t go to university.’

(The perfect irony when you consider that art begins with the brain.)

After school, she took on a series of jobs – ‘God, a whole bunch of them!’ – including post-lady, supermarket worker, cleaner.

‘I finally realised that waiting for something to happen wasn’t an option. So I decided to go out and find a solution myself.'

She enrolled at art school in Holland – and found a similar set of rules to the ones she had rebelled against in school. Changing tack, she opted to spend the summer at an atelier in Florence. ‘Straightaway I thought: That’s what I want to do.’

After Florence, Lizet joined LARA in London, which was teaching the traditional drawing and portrait skills she was hungry to learn.

‘When I arrived, they were just setting up in this giant old factory, which was absolutely freezing. Single-glazed windows with cracks. Concrete floor. We would strap hot-water bottles to ourselves, front and back, and wear fingerless gloves so we could still draw. Looking back, I don’t know why we accepted it! But we all wanted it so badly.’

London, despite the financial strain of living in a capital city, was a welcome eye-opener, too.

‘Funnily enough, you think the Dutch are very open-minded, but it felt like there were a lot of social rules in Holland. In London, what I really liked was the way people would look a certain way and act completely differently. There was no correlation. You just couldn’t judge someone based on how they dressed.’

*************

In August 2019, fellow LARA student, Neil Davidson, set up Raw Umber Studios, the not-for-profit art school and studios now based in Stroud. Lizet ran its inaugural workshops.

Then lockdown changed everything. LARA folded; and, at Neil’s suggestion, Lizet began to lead online portrait-drawing tutorials to help people through lockdown. ‘I was still in my studio-flat in London, at the time, so I had to do the filming in a tiny communal mouldy corridor with 100-year-old carpet and people walking constantly by! But we got a load of videos done – and it was fun to do a new project.’

When Raw Umber Studios moved its base to a converted church in Stroud in the summer of 2021, Lizet came for a short visit. ‘And discovered how absolutely lovely it is around here. I rented a flat pretty much straightaway.’

Today, as artist-in-residence, she’s continuing with online tutorials – students view them from all over the world – as well as in-person classes.

And she’s pursuing her own work – portraits, landscapes. ‘A bit of everything.’ Constantly defying expectations.

‘I did think it would be really fun to paint raw chicken. Who likes looking at raw chicken? Nobody. I think it’s a good reason to paint it. With social media, particularly, you get a limited view of what’s good and what’s bad; what’s pretty and not pretty. One thing that I love about art and artists is those rules aren’t really there. Somebody who could be considered ugly by traditional standard is massively interesting to paint. And I love that.’

But – again – don’t define her as Lizet-Who-Paints-Dead-Things. It’s not about the goal; it’s not about having something specific to say or a style that describes her.

‘We had a really good workshop here at Raw Umber with Nicholas O’Leary, where he said that painting, for him, wasn’t about having a ‘voice’. It was just a way to experiment. That was enough.

‘It’s great to meet artists who have their own view. But it was really inspiring for me to hear Nicholas say that. That’s exactly how I feel. It might sound stupid, but I felt that what he said gave me permission to feel that way, too.’